Enterprise-Scale Open Source Email Systems

Large-scale email systems differ noticeably from their smaller brethren. An email installation for a thousand or so users asks fewer questions than one that has to support tens of thousands, even if the range of facilities offered is much the same. Before looking at the particular questions posed by large installations and their need for scalability it's worth investigating what any decent email system should support.

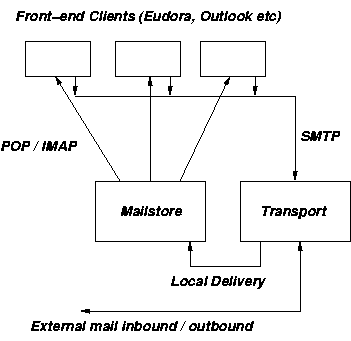

There's a wide range of shapes and sizes of email packages for the modest user. Most are based around a common concept: the mailstore and transport (the 'back-end') which is implemented independently from the front-end client software (what the human user will use to compose and read the messages with), both parts communicating through standardised protocols. Because there are indeed well-established standard protocols to use, it's common to find a diverse mixture of client packages all using the same back-end. Popular mail clients include such well-known pieces of software as Outlook, Pegasus, Eudora and their many competitors.

Understandably, most people know far less about their back-end systems than their front-end client packages. If you use Outlook all day at work, you probably neither know nor care whether it's talking to Microsoft Exchange or a Unix system using an IMAP server; that's the beauty of standards. There are numerous software solutions for small to medium-scale back-end services.

Open Standards Support Mix and Match Integration

This use of standard protocols allows email system designers to play mix-and-match with the various components of the system. This is counter to the interests of those who would like to establish a monopoly on enterprise software, so you will often find that the back-end systems also provide a unique and non-standard set of features which will only work with 'preferred' mail clients. The additional features will be intended to hook the users in ways that make it much harder to replace that particular vendor's back or front end with a competing product. Integrated groupware services such as calendar and address book facilities are typical and popular examples.

Once the proprietary hooks have taken effect it CAN be hard to switch, but with a will (after all, at the end of the day it's only email) it remains possible, though at the cost of losing those nifty lock-you-in features or having to implement them in different ways.

Fortunately, because of the need to work in mix-and-match environments, all of the popular client packages are able to interwork with back ends that conform to the important standards, which in this case are SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol), POP (Post Office Protocol) and IMAP (Internet Message Access Protocol) together with a modest range of lesser standards. IMAP is nowadays the preferred way of accessing user's mailboxes with POP being rather old-fashioned and restrictive in what it permits. The diagram may help to show how the parts fit together

Anyone who wishes to build an email system that conforms to the standards has a wide range of software packages to choose their back-end services from. All of them provide support for the standard protocols but vary considerably in the management and ancillary services that they supply such as address books / directories, virus filtering, spam filtering and so on.

One of the simplest configurations to build is one which has the back end components on a single server. In that case the mailstore will often use simple files to store the email and local delivery from the transport service is no more complicated than copying the email message into the relevant file. For user populations of a few hundred up to (depending on load) maybe a thousand or so accounts, a well-configured single server will usually be all that is needed.

Open Source Provides Open Standard Options

In the Open Source world the key components for email are well-established.

The three most popular mail transport agents are probably Sendmail, Postfix and Exim. All three are capable of heavyweight

performance and are regularly used by Internet Service Providers (ISPs) for

very large user populations. In the single-server configuration on a typical

Linux installation they will automatically deliver mail into user's mailboxes

(commonly a single file) for each account that is configured on the server. For

example, if a user has a login name of user345 on a server configured

to receive mail for sampledomain.com then mail addressed to

user345@sampledomain.com will be delivered to that user's mailbox

without any extra configuration being needed. To turn on POP/IMAP services

will be the work of a few more moment's configuration and then you have a basic

email system capable of serving the needs of many small to medium sized

businesses for little more than the cost of a Linux disk and a mid-level

server. To add users it's just a matter of creating a login account for them on

that system.

The basic configuration is a reasonable get-you-started solution but it lacks a lot of bells and whistles. A 'serious' IMAP service will provide support for shared folders, access control lists saying which users can see which folders, quotas on mailbox sizes and various administrative tools to ease the process of running the service. Enterprise class users are also likely to want virus filtering and content filtering services to be provided. There also needs to be a better way of establishing user accounts than having to manually create an account on the server, it is better if logins on the server and email accounts are unrelated.

Cyrus IMAP Server

The quick and easy IMAP service provided with basic Linux installations typically doesn't have the full range of enterprise features. More complex IMAP services do exist, the leader in the field being the Cyrus IMAP server from Carnegie Mellon University. A number of popular packages both commercial and non-commercial are based around Cyrus.

Directory Services: OpenLDAP vs. Active Directory

Directory services are typically be constructed around LDAP, the "Lightweight Directory Acess Protocol". This is used by commercial, proprietary systems such as Microsoft Active Directory as well as having Open Source implementations (the clear leader is Open LDAP). Open LDAP is a core component of just about every Open Source email package. LDAP directories can be used for much more than mere address lists and will often also be the repository for information about local users on the email system. To create a new email account on the email system the administrator might use an administrative command to create a new local user and the email system would then enquire about that user's existence and attributes via the LDAP service.

An near-enterprise class email solution can be put together from well-known and widely tested Open Source Components. A typical configuration would be Postfix, Cyrus, Open LDAP and maybe Spam Assassin for spam filtering. Content and virus filtering is less straightforward, since anti-virus packages are in the main only proprietary and will require a subscription.

Whilst anyone with moderate skill and the ability to read documentation can put together a fully-functional email solution from the Open Source components listed above, the question has to be asked as to whether it's worth the cost of the time. By the time it has been packaged and the administrative 'glue' been added to make it easy for non-expert users to configure and manage such a combination, many hours will have been spent. That's why most of the commercial organisations supporting and distributing Open Source software sell their own enterprise email solutions which, though based on the widely available core components, come with the supporting elements to make them easy to deploy and use. The modest cost of these commercial variants is usually well worth paying. At the time of writing, to pick just one example, the SuSE SLOX (SuSE Linux Open Exchange Server) email solution costs in the region of US $1,000 all-in for a single server and attracts no client licence fees at all unless the additional (proprietary) groupware features are used. On a mid-range server costing, say, another US $1,500, that will serve a user population of somewhere between a hundred up to a thousand depending on how much use they make of it (there is no particular upper bound).

Scalability

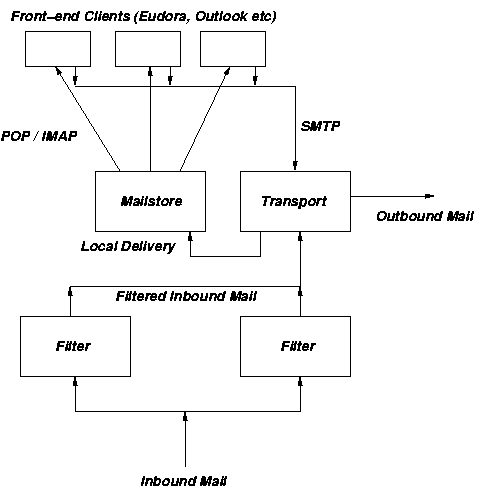

The difficulties start to come when you need to scale an email system to hundreds or thousands of heavy users. Spam and virus checking are demanding processes so the first step is often to offload those tasks to a number of separate servers and then to funnel the checked mail to a configuration identical to the lower-load solution. Arranging to load-balance incoming mail can often be done using round-robin DNS tricks, which whilst not perfect is usually workable (with round-robin the DNS serves up multiple addresses and the client picks from amongst them). If outbound mail also needs to be checked and filtered a similar approach can be taken, though the diagram would look different.

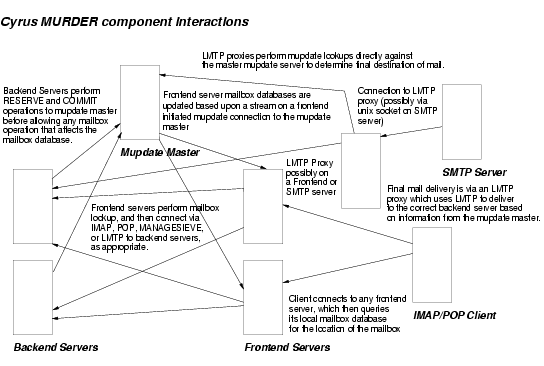

Eventually the load starts to become too much for a single mailstore and then a clustered solution is required. Other solutions may exist, but the one that we are familiar with is the one that comes with Cyrus. It permits seamless use of multiple servers to handle incoming IMAP requests and then dispatching them to one of various mailbox servers, yet to the outside world still looks the component in the diagram labelled 'mailstore'. Rather alarmingly it's known as murder, after the collective noun for a group of crows. The offical description of the software can be found at the Cyrus website

The Murder aggregator takes the mailstore component and splits that into

components also known as front and back ends. The aggregator front ends are

arranged in a load-balanced configuration so that mail clients can connect to

any one at any time. The aggregator front ends communicate with a master

controller so that they know which aggregator back end contains the mail for

the operation currently being undertaken. The aggregator back ends contain the

mail messages and communicate with the master controller to keep it informed of

changes. Overall the processing is split across multiple servers each

undertaking a share of the work involved and as a consequence the system is

scalable to a large number of servers. To give an idea of the scale of system

that can be supported, Carnegie Mellon University publish statistics indicating

that with five aggregator front ends and 4 aggregator back ends they serve a

population of 26,516 user inboxes (i.e that many distinct users), 203,069

mailboxes in total and according to the graphs at http://graphs.andrew.cmu.edu/, a load

of something over 10,000 simultaneous users at peak times (the bulk of the

working day). The Murder project illustrates the arrangement of the aggregator

with the following image:

Case Study in Murder!

As an example of a Cyrus Murder implementation, we (GBdirect), working in collaboration with Total Solutions in Ipswich installed a three-server system at an educational establishment in the east of England. The user population consists of one thousand academic users and ten thousand students, all of whom have mailboxes provided on the system. The institution had previously been using a Microsoft Exchange email system but this had in the past proved to be unreliable and difficult to maintain. Furthermore, extending the system to a population of some eleven thousand would have been very expensive in terms of client access licences.

The institution makes extensive use of Microsoft Active Directory Services and did not wish to introduce another form of user directory to store identities and passwords, so the Cyrus system was required to obtain user authentication (username and password) from the Active Directory service. Fortunately, the flexibility of Linux and the Cyrus software made this relatively painless.

Using Active Directory to obtain authentication means that users of the system don't have to remember a separate username and password just for the email system. Administrators can manage users via the Active Directory service and the Cyrus email system will 'just work' for the users without any obvious seams being visible. Most of the users will be using Outlook, though a mixture of other email clients are also available. A web-based email system based on the free Squirrel Mail gives all the users secure access to their mail from any web browser.

The mail system is implemented on IBM servers running SuSE Linux. A single front-end server running Postfix and the front-end Murder aggregator receives the mail, dispatching it to two back-end servers acting as clustered mailstore. As well as proprietary virus filtering, the front-end server uses the free Spam Assassin spam filter running in server mode. The files for the mailstore are stored on a Storage Area Network (SAN) with fibre channel cards in each server.

Though not related to the email system, members of the institution also have access to their own web space and ftp services which are also authenticated against Active Directory.

The next stage in the rollout will be to install Nagios network monitoring software as part of the overall network monitoring and management and to keep an eye on load levels and disk usage levels on the mail servers. The servers are managed locally through the use of SuSE's YaST client management tool as well as Webmin and Open SSH for remote systems management.

The system installation took two days on-site with additional configuration performed remotely. Support for the system is now ongoing.